Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

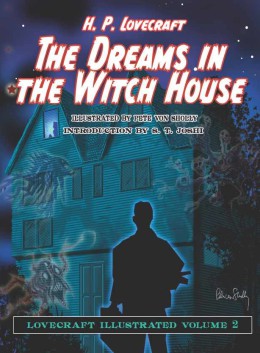

Today we’re looking at “The Dreams in the Witch House,” written in January and February 1932, and first published in the July 1933 issue of Weird Tales. You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead.

“He seemed to know what was coming—the monstrous burst of Walpurgis-rhythm in whose cosmic timbre would be concentrated all the primal, ultimate space-time seethings which lie behind the massed spheres of matter and sometimes break forth in measured reverberations that penetrate faintly to every layer of entity and give hideous significance throughout the worlds to certain dreaded periods.”

Summary: Walter Gilman, Miskatonic University student, has begun to trace a connection between ancient folklore and modern mathematics and physics. He studies the Necronomicon and Book of Eibon until professors cut off his access. But they cannot stop him from renting a room in the house that once belonged to Keziah Mason. Keziah appeared before the Salem witchcraft court of 1692, admitting allegiance with the Black Man. She claimed to know lines and curves that led beyond our world, then escaped from her cell leaving such patterns on its walls. This legend fascinates Gilman.

He doesn’t mind rumors that Keziah and her rat-like familiar Brown Jenkin still haunt her house. In fact, he selects the very attic room in which she practiced her spells. It’s irregular, with one wall sloping inward and the ceiling sloping downward, so the two skewed planes create singular angles. They also create a loft between the roof and the outer wall, but this space has long been sealed off and the landlord refuses to open it.

Whether it’s the dark atmosphere of Arkham or the wildness of his studies, Gilman falls into feverish dreams of plunging through abysses of “inexplicably colored twilight and bafflingly disordered sound.” Queer-angled masses people the abysses, some inorganic, some living, and his own physical organization and faculties are “marvelously transmuted.”

From these “vortices of complete alienage,” his dreams shift to visions of Brown Jenkin and his mistress Keziah, approaching closer and closer. His hearing grows uncomfortably acute, and he hears scratching in the loft above. In class he concocts outlandish theories. With the right mathematical knowledge, a man might pass through the fourth dimension into other regions of space. For some reason, Gilman’s convinced transition would only mutate our biological integrity, not destroy it. And in some belts of space, time might not exist, so that a sojourner could gain immortality, aging only on jaunts back into “timed” space.

Months pass. His fever doesn’t abate. Polish lodgers say he sleep-walks and warn him to guard against Keziah and the coming Walpurgis season. Gilman shrugs them off, but worries about a crone he’s seen in the streets. In his dreams the crone—Keziah—appears from that weirdly angled corner in his room. He intuits that she and Brown Jenkin must be the iridescent congeries of bubbles and the small polyhedron that lead him through the extraterrestrial abysses. Awake, he’s troubled by a pull towarddifferent points in the sky, and one dream takes him to a terrace under three suns. An alien city stretches below. Keziah and Brown Jenkin approach with alien beings, barrel-shaped and star-headed. He wakes to the smart of sun burn; later the landladydiscovers a metal image in his bed, barrel-shaped and star-headed, and Gilman remembers breaking the ornament from the terrace balustrade in his “dream.”

The next “dream” finds Gilman in the loft over his room, a witch’s den of strange books and objects. Keziah presents him to a huge man with black skin, in black robes, who wants him to sign a book. Keziah provides the quill. Brown Jenkin bites Gilman’s wrist to provide the blood. He faints in “dream” but later half-recalls a further journey into black voids, along “alien curves and spirals of some ethereal vortex,” into an ultimate chaos of leaping shadows and monotonously piping flutes. He wakes with wounded wrist.

He seeks help from fellow student and lodger Elwood. They take the image to professors, who cannot identify it, or even all the elements in its alloy. Elwood lets Gilman sleep in his room, but Keziah still drags him off to an alley where the Black Man waits, Brown Jenkin frisking about his ankles. Keziah snatches a baby from a tenement. Gilman tries to flee, but the Black Man seizes and strangles him. The marks of his fingers remain in the morning, and the papers report the abduction of a child from a Polish laundress. The Poles are unsurprised—such abductions are common at dangerous times like the impending Walpurgis sabbat.

April 30, Walpurgis Eve, finds Gilman in Elwood’s room. He hears the pulse of reveling worshippers who supposedly meet in a ravine near Arkham. The same rhythm beats in the abysses through which Brown Jenkin leads him. They emerge in the loft, where Keziah is about to sacrifice the stolen child. Gilman feels compelled to assist, but fights free. He strangles Keziah with the chain of a crucifix one of the Polish lodgers has pressed him to wear. But Brown Jenkin gnaws open the child’s wrist and collects its blood in a metal bowl. Gilman kicks the familiar into the gap between floor and wall. He then dares an unassisted plunge through the abyss, in spite of the crescendo of the universal Walpurgis rhythm.

The next day a doctor finds Gilman’s eardrums burst. And though he may have killed Keziah and injured Brown Jenkin, the rat-familiar visits him that night to gnaw into his chest and devour his heart.

After this horror, the Witch House is closed. Years later, a gale wrecks the roof. Workmen find the loft space collapsed, to reveal infant bones both recent and ancient, the skeleton of an old woman, and occult objects. They also find Gilman’s crucifix and a tiny skeleton that baffles Miskatonic’s comparative anatomy department. It’s mostly rat, but with paws like a monkey’s and a skull blasphemously like a human’s.

The Poles light candles in St. Stanislaus’ Church to give thanks that Brown Jenkin’s ghostly titter will never be heard again.

What’s Cyclopean: The alien city of the elder things, that Gilman visits while learning to navigate the void.

The Degenerate Dutch: As usual, Lovecraft wants to have his cake and eat it too about “superstitious foreigners” whose superstitions are 100% correct.

Mythos Making: Nyarlathotep sure does spend a lot of time trying to convince people to leap sanity-destroying voids. This is the first time he’s needed anyone to sign a consent form, though. (Or maybe the Black Book is more along the lines of a EULA?). Plus cameos by elder things and Azathoth.

Libronomicon: Dark hints about the true nature of witchcraft can be found in the Necronomicon, the fragmentary Book of Eibon (did we know before that it was fragmentary?), and the suppressed UnaussprechlichenKulten (which suppression is traced in more detail in “Out of the Aeons”).

Madness Takes Its Toll: Seriously, don’t leap sanity-destroying voids. Never mind the fascinating xenopsychological opportunities to be found in cyclopean alien cities.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Somehow I always remember this story as relatively peripheral to the Mythos—I think because it lacks the serious alone-time with scary aliens that makes so many later stories stand out. But this one has both shivers and extensive Mythosian worldbuilding, even if they don’t make quite the impression in my memory as the Yith or the Outer Ones.

Witchcraft, in its historical imagined-by-nervous-Christians sense, is a thread that runs through all of Lovecraft’s work. Find a creepy old dude working black magic, or a young dude a little worried about his family history, and you can be sure of a line mentioning an ancestor hung in Salem. Chat about comparative religion with an alien from beyond the stars, and you’ll find that they celebrate Beltaine and full moon rituals—all things considered, it’s quite possible that the Mi-Go smell of patchouli incense and have strong opinions about the relative merits of the Rider-Waite and Robin Wood tarot decks. Here, we get some explanation of why: all these ancient rituals (and, I guess, the Earth’s orbit) are shaped by the monotonous drumbeat rhythms at the endless prom of the mindless Other Gods.

Which is… kind of cool, actually. And sure, those rhythms may deafen and madden anyone who hears them unfiltered, but the idea of some sort of order, however horrific, connecting such disparate species, is pretty tempting.

And also runs counter to every cosmic horror claim about a mindless, meaningless universe. WTF, Howard? In fact, this whole story kind of undermines the Mythos’s existentialist purity. Not only are there rhythms binding the whole universe together, not only does Nyarlathotep get signatures of approval from participants in his dastardly doings, not only does child sacrifice actually appear to be of interest to inhuman, mindless entities—but a common cross actually does some good. Woe to all who have spoken contemptuously of the Derlethian heresy, for here it is in its original form. Gilman may ultimately go mad, but he does so because he tries to get home under his own power and because Brown Jenkin is a resilient little beast, not because his cheap talisman doesn’t have an effect.

Speaking of Gilman, that’s an interesting name to pop up here, isn’t it? Is he descended from some distant cousin of Innsmouth, inheriting only a weird fascination with the occult? Or are Kezia and Nyarlathotep interested in him for some reason other than his bad taste in apartments? Someone who might serve you for a couple of billion years—that would be quite a catch for the Black Book.

Getting back to the Mythosian worldbuilding, one aspect that’s a lot more in keeping with what we see elsewhere is the vital role of mathematics. Math and folklore: definitely the most interesting majors at Misk U. Beware anyone studying both. Folklore tells you what you’re doing and why it’s a bad idea; math tells you how to do it anyway.

Lovecraft, of course, was not a big math fan—as evidenced here by his mention of “non-Euclidean calculus.” Mathematicians among the commenters are welcome to share insight, but Google and I both agree that while geometry can certainly be non-Euclidean, calculus is sort of orthogonal to the whole business (so to speak). Yet somehow, his suggestion that math will open up the vast sanity-threatening vistas of the cosmos—not to mention his portrayal of class sessions devoted to discussion of same—make the whole subject seem a lot more appealing. I’m actually pretty fond of calculus myself, but the most I got out of my college classes was a better understanding of epidemiology, and an introduction to They Might Be Giants.

Anne’s Commentary

August Derleth’s negative response to “Witch House” appears to have hit Lovecraft hard. He semi-agreed with Derleth that it was a “miserable mess” and refused to submit it for publication. Ironically, or maybe characteristically, Derleth himself submitted the story to Weird Tales, which published it. That proved Derleth’s original contention that though “Witch House” was a poor story, it was saleable. Lovecraft felt the difference between “saleable” and “actually good” was indeed an important thing, “lamentably” so, and wondered if his fiction writing days were over. Not so much—the magnificent “Shadow Out of Time” was yet to come and, at its greater length, would deal more effectively with similar cosmic topics. So, yeah, “Witch House” is a bit of a jumble, cramming in all sorts of ideas Lovecraft had gleaned from those “utmost modern delvings of Planck, Heisenberg, Einstein and de Sitter.” Add in the New England Gothic setting of Arkham at its most brooding and festering, clustering and sagging and gambrelling, all mouldy and unhallowed. It’s a fictive emulsion that sometimes threatens to destabilize, the new physics SF separating from the dark fantasy.

I still like it pretty well. It’s like Randolph Carter discovering that what happens in dreams doesn’t stay in dreams. Lovecraft is careful to let us know that Walter Gilman’s sleep-travels are in-body experiences, with waking world sequelae. Somehow Gilman is sure that a man could travel into the fourth dimension, mutating to suit the higher plane, without physical harm. Why? Because he’s done it himself! When naughty Brown Jenkin bites Gilman, Gilman wakes bitten. When he transdimensionally travels to a three-sunned planet, he wakes up with a hell of a sunburn. Plus he brings back a souvenir in the form of a metal ornament containing unknown elements! It’s the next step forward in time-space travel, with a tempting immortality option to boot. Keziah and Brown Jenkin, it turns out, aren’t ghosts. They’re as lively as they were back in 1692, thanks to spending most of their time in timeless regions where they don’t age. At least that’s what Gilman implies in conversation with Elwood.

It’s almost a throwaway bit of speculation, though, occurring more than halfway through the story in the drowsy chat of the two students. I imagine Lovecraft suddenly thought, “Damn, don’t I have to kind of explain how Keziah and Brown Jenkin could still be around, alive, 235 years after the witch trials?” Other bits gets thrown in willy-nilly, as if too tasty to exclude. One is the sleep-trip to the ultimate black void where flutes play and Outer Gods dance and Azathoth lolls. This is the kind of excursion that’s supposed to blow one’s sanity to utter rags, but Gilman doesn’t make much of it. Another is the trip to the three-sunned planet, very tasty in itself, especially since it brings in the star-headed Elder Things we grew to love so well in “At the Mountains of Madness.” Why–has Gilman come to their home-world? And how cool is that? But again, not much connection to the main story beyond giving an example of how far fourth-dimensional travel can take one.

Any day Nyarlathotep shows up is a good day, in my prejudiced opinion. For the Puritans, Satan could take many forms, from animal (white bird, black cat, small deer) to human (a black man with the traditional cloven hooves.) The Black Man is thus a suitable avatar for Nyarlathotep to assume among Puritans, as Lovecraft suggests here—very awe-inspiring, one assumes. Lovecraft is careful to tell us this is not just a big African man, though on two occasions witnesses and police will mistake him for one at a glance. He is “dead black”—I guess coal or onyx black, an unnatural hue for human skin. His features are not “negroid.” I’m not sure we’re supposed to make any more of this than that the guy is NOT human. Lovecraft’s oddly coy about the hooves, however. They’re hidden behind a table, then in deep mud. Then their prints are compared to marks that would be left by furniture feet, oddly split down the middle. Why not just say they look like goat hoofprints? Couldn’t Gilman’s brain make that jump by this point?

Got a quibble, too, with Nyarlathotep strangling someone with his bare avatar hands. Come on, he’s Soul and Messenger of the Outer Gods! He must know a few good paralysis spells, should he want to stop someone from fleeing.

Brown Jenkin, on the other hand, is thoroughly awesome. He titters. He gnaws. He freaking NUZZLES PEOPLE CURIOUSLY in the black hours before dawn! This puts him on creep-out par, in my book, with that dreadful dreadful thing in M. R. James’s “Casting the Runes,” which hides under pillows, with fur around its mouth, and in its mouth, teeth.

Next week, we sail on “The White Ship.” This takes us to the safe part of the Dreamlands, right?

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land and “The Deepest Rift.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. The second in the Redemption’s Heir series, Fathomless, will be published in October 2015. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.